Aluminum Forging

Aluminum forging is a method for processing aluminum alloys using pressure and heat to form high strength, durable products. The process of aluminum forging involves pressing, pounding, and...

Please fill out the following form to submit a Request for Quote to any of the following companies listed on

The content of this article provides detailed information about forging steel.

You will learn:

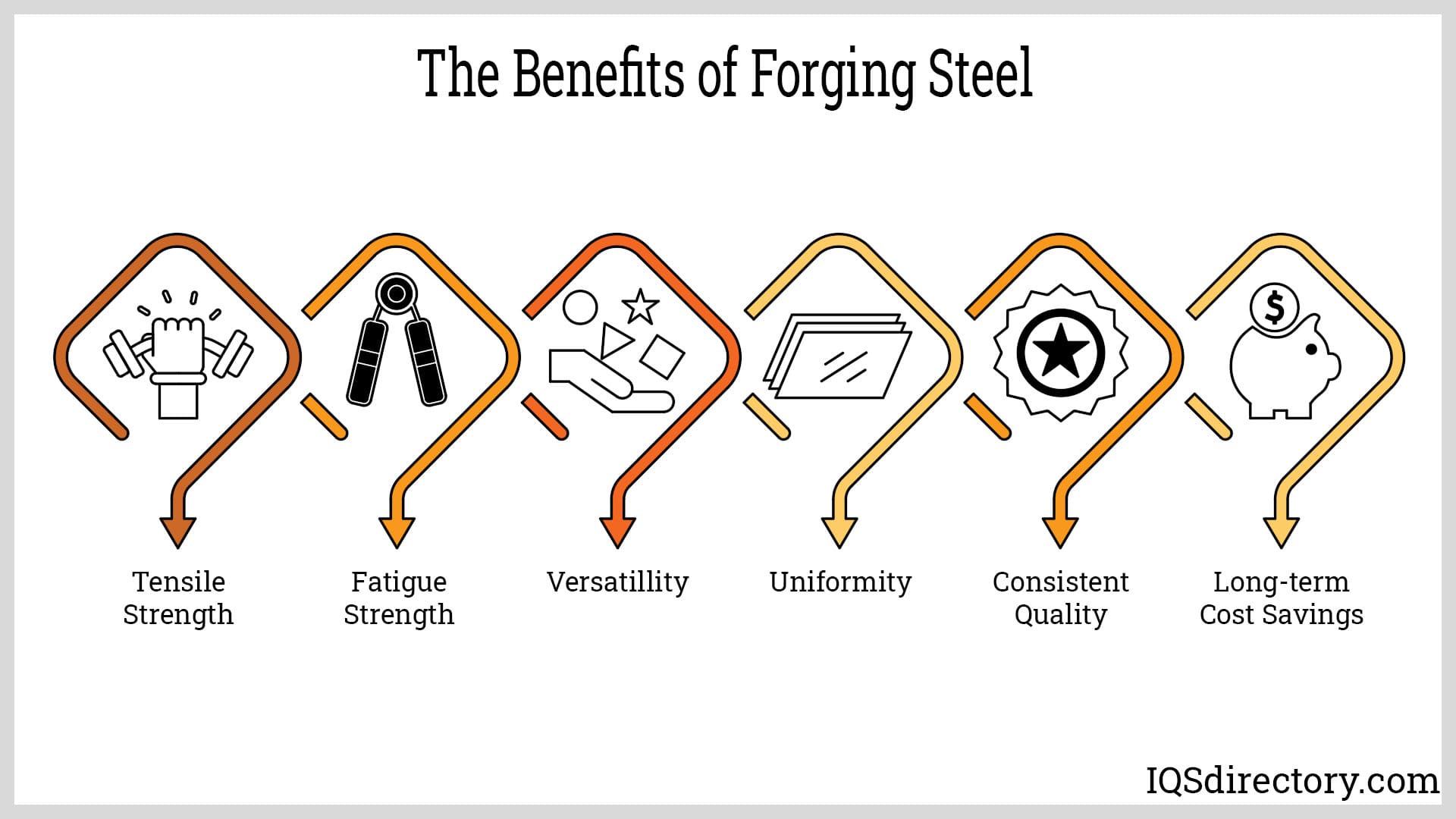

Forging steel is a production technique that molds steel through localized compressive forces, such as hammering, pressing, and rolling. This method is often utilized to create top-quality steel components with precise tolerances. Steel destined for forging is produced by mixing iron and carbon under managed pressure conditions to achieve optimal ductility, fatigue resistance, tensile strength, and superior grain structure.

The process of forging steel is divided into three main categories: cold, hot, and hardened, each defined by the specific temperatures and pressures used in forming. This shaping approach gives forged steel distinctive qualities that distinguish it from cast steel, such as improved solidity, anisotropy, and uniformity.

The forging process enhances the strength of the metal, making it perfect for mechanical and industrial use. Forged components are highly reliable, thanks to their consistent composition and structure, making them well-suited for enduring significant loads and stress. Moreover, they are free from voids, pockets, and other imperfections that might lead to load failure.

Understanding the forging steel process is crucial when evaluating industrial metalworking methods or sourcing high-performance steel components. Do all forging steel processes follow the same form, involving the application of force to a steel billet that is either heated or processed at room temperature? How does forging steel differ based on hot forging, cold forging, and warm forging techniques? How does the temperature at which forging is completed depend on the processing type, including the use of forging dies, hydraulic presses, mechanical hammers, rollers, and other forging equipment? Is the key factor in every method truly the application of compressive force and the ductility of the steel billet, or do alloy composition and forging environment also affect the final properties of forged steel products?

Successful forging steel, like all precision manufacturing processes, always starts with robust design and careful engineering planning. For closed die forging or impression die forging, engineers develop a die configured to the finished shape, taking into account metal flow and desired tolerances. Open die forging, roll forging, and press forging processes also rely on detailed part drawings and simulations to determine how the forging force will be applied to the billet. CAD models, forging simulation software, and metallurgical analysis are now progressively utilized to predict deformation, reduce material waste, and optimize the microstructural properties of forged steel components. This foundation is essential for manufacturing steel products that meet specific performance standards for strength, fatigue resistance, and durability.

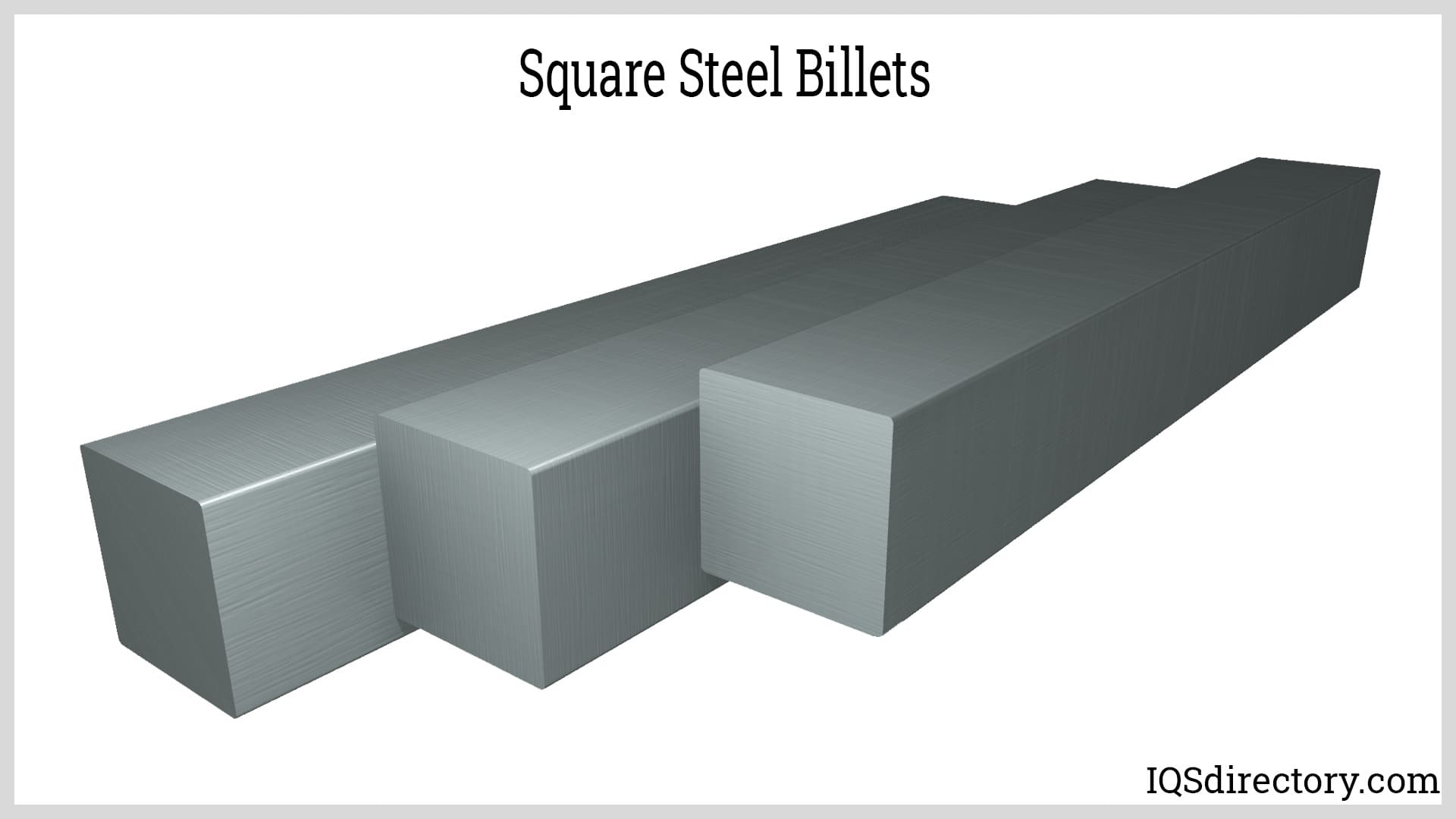

Billets—produced through hot rolling, continuous casting, or extrusion—form the raw material base for forging. These steel billets, typically in square or rectangular cross-sections with uniform dimensions along their length, are essential for producing a wide range of industrial and automotive parts. Before starting the forging process, billets are cut to lengths matching design specifications, ensuring consistency in weight and volume for each forged component. Selecting the appropriate steel grade for forging is critical; billets are classified by alloy content (such as carbon steel, alloy steel, or stainless steel), carbon percentage, and grain microstructure. The selection process takes into account end-use requirements, such as corrosion resistance, weldability, and desired mechanical strength. Precision billet cutting ensures minimal waste and optimal forming during subsequent forging operations.

Temperature plays a defining role in determining the forging method for steel. Billets may undergo heating—as in hot forging and warm forging—or be shaped at or near room temperature in the cold forging process. In hot forging, the billet is heated above its recrystallization temperature (typically between 900°C and 1250°C) to maximize ductility and malleability, minimizing forming force requirements and enabling complex geometries. Processes such as die forging, open die forging, and precision forging commonly use hot forging techniques, which result in refined grain structure and improved impact resistance. By contrast, cold forging operates at ambient temperatures and requires greater applied force but produces superior dimensional accuracy, surface finish, and material strength due to strain hardening. Warm forging represents a hybrid, conducted at moderate temperatures, offering a compromise between high strength and formability while reducing forging loads. Selecting the optimal forging temperature is based on material grade, part complexity, and desired performance characteristics.

Multiple steel forging methods ensure that manufacturers can meet a diverse array of product and performance demands. The most widely used processes include:

These processes differ in terms of pressure application, die configuration, and achievable part complexity. Forging steel enables the manufacture of high-strength structural parts—ranging from aircraft landing gear, jet engine shafts, turbine blades, gears, mining machinery, to hand tools like chisels, screws, and bolts—where superior strength, fatigue resistance, and structural integrity are vital.

The finishing stage of forged steel parts is integral to meeting surface texture and dimensional specifications required by most industries, including automotive, aerospace, and oil & gas. Finishing processes such as grinding, flash removal, surface polishing, buffing, and precision CNC machining eliminate surface defects, smooth sharp edges, and achieve final dimensions. The choice of equipment and methodology depends on whether the forging process was open die or closed die, as well as the functional and aesthetic standards set by the customer. High-precision secondary machining is often applied to critical tolerances on shafts, gears, and bearing surfaces for optimal performance in demanding environments.

Shot blasting is an aggressive mechanical finishing technique, where forged steel parts are bombarded with metallic beads, sand, or other abrasives. This process removes surface scale, oxide layers, heat-treat discoloration, and other impurities left over from forging. Shot blasting not only achieves a significantly clearer and smoother finish compared to hand deburring, but it also enhances paint or coating adhesion by creating an ideal surface profile. This step is especially valued when corrosion protection and surface appearance are critical in automotive and structural components.

Applying heat treatment to forged steel components is essential for optimizing their mechanical properties, including tensile strength, toughness, hardness, and ductility. Manufacturers use a variety of heat treating processes—selected based on part function, size, and desired performance characteristics. Heat treatments such as normalizing, quenching, annealing, tempering, and spheroidizing further refine steel’s crystalline structure and performance metrics.

The final stage of the forged steel manufacturing process involves a range of surface treatment technologies designed for both function and appearance. Basic cleaning steps, like washing with water, oil, or chemical baths, remove residual contaminants. More advanced surface treatments, including zinc plating, hot-dip galvanizing, electroplating, powder coating, and industrial painting, are chosen according to the part’s end-use environment. These treatments add corrosion resistance, enhance wear properties, and satisfy strict industry standards in sectors such as automotive, energy, and heavy equipment manufacturing. The optimal surface treatment is determined by the forging’s geometry, expected service conditions, and customer specifications, ensuring long-term durability and reliability for every forged steel product.

Selecting the optimal alloyed steel for forging processes is essential in modern manufacturing, as alloying elements dramatically enhance the resulting steel's physical and mechanical properties. Forging-grade steel must meet stringent demands for hardness, yield strength, impact toughness, tensile strength, high-temperature stability, corrosion resistance, and wear resistance. The most commonly used alloying elements in forging steel include boron, chromium, molybdenum, manganese, nickel, silicon, tungsten, and vanadium. These elements serve to manipulate structural composition, optimize grain formation, and reinforce desirable attributes needed for industrial and automotive forging applications. Additionally, less frequently implemented alloys—such as aluminum, cobalt, copper, lead, tin, titanium, and zirconium—play targeted roles in improving machinability, weight reduction, or specialized resistance properties.

There are over 57 recognized types of steel, each engineered for distinct industrial uses and defined by the percentages and combinations of alloying elements, ranging from trace amounts to upwards of 50% of the total steel composition. For clarity, steels are typically classified by alloy content: high alloy steel refers to steels with more than 8% alloying elements (by weight), while low alloy steel falls below this threshold. Understanding these distinctions is critical for selecting the right forging materials that satisfy performance requirements in aerospace, oil & gas, toolmaking, and construction sectors.

Carbon plays a foundational role in defining steel's performance characteristics. In alloyed steels, carbon typically makes up around 0.35% of the composition—though this varies based on the application and steel category. Increasing carbon content enhances surface hardness, tensile strength, and hardenability—critical attributes for parts like forged fasteners, gears, and shafts. Nonetheless, excessive carbon also raises brittleness and reduces weldability due to the formation of harder microstructures such as martensite, impacting the steel's ductility.

Carbon steel is typically classified into three groups: plain, low, and high carbon steels. Plain carbon steel contains less than 1% carbon and small amounts of other alloying agents like manganese, phosphorus, sulfur, and silicon. Low carbon steel (also referred to as mild steel), contains less than 0.25% carbon and is alloyed with elements such as nickel, chromium, molybdenum, manganese, and silicon. This improves strength, ductility, impact resistance, and facilitates low-temperature applications common in forging automotive components and piping.

High alloy steels are exemplified by stainless steels, renowned for their corrosion resistance attributed to chromium content of at least 12% and significant quantities of nickel. Stainless steel grades are grouped into martensitic, ferritic, and austenitic types. Ferritic stainless steel boasts the highest chromium ratio (12%–27%) and excellent resistance to oxidation and scaling—a valuable property for forging tools, medical devices, and food processing equipment. These characteristics have made stainless alloys indispensable for applications demanding durability, minimal maintenance, and resistance to harsh environments.

The SAE numbering system is a globally-enforced standard for distinguishing different types of carbon steel and alloy steels. Using a four-digit nomenclature, the SAE system provides instant recognition of the primary alloying content and approximate carbon percentage—making material selection for forging and machining far more precise. For instance, the first digit identifies the steel category (1: carbon steels, 2: nickel steels, etc.), while the subsequent digits further specify alloy makeup and carbon content. Designations such as 10XX indicate plain carbon steels, while 11XX and 12XX denote resulfurized and rephosphorized steels, respectively, which are specialized for improved machinability.

The second digit in the SAE code details the major alloying element, with a zero indicating normal sulfur content—crucial for machining efficiency. The final two digits report the carbon content in hundredths of a percent. Additional letters in the sequence, like “L” for lead and “B” for boron, indicate enhanced machinability or other specific properties. The suffix “H” is used to flag steel with elevated hardenability, critical in components subject to high thermal or mechanical stresses.

Initial SAE designation numbers:

While the SAE/AISI steel grading system is prevalent for alloy identification and selection in North America, other industry standards and classification systems are also in use globally, such as:

Being familiar with regional and application-specific standards—such as ASTM, EN (European Norm), and JIS (Japanese Industrial Standards)—ensures correct material selection across international supply chains and compliance with quality assurance protocols.

The manufacturing method of alloy steels directly affects critical material properties such as structural uniformity, internal purity, and suitability for specific forging techniques. Despite technological advances in steel production, the main phases of alloying for forged steel remain consistent, emphasizing precise control of chemical composition, temperature, and cooling rates throughout the process.

Each step is carefully monitored to ensure chemical consistency and prevent introduction of defects that could compromise forged part performance. Leading forging companies may also apply advanced metallurgical techniques such as vacuum degassing, argon oxygen decarburization, or electroslag remelting to achieve premium steel grades for aerospace, automotive, and heavy industrial applications.

Alloy steels are the backbone of forged components across heavy industry and manufacturing, favored for their cost effectiveness, broad availability, ease of processing, and adaptability to heat treatment and thermal/mechanical processing. Their customizable mechanical properties—such as improved hardness, tensile strength, ductility, toughness, corrosion resistance, and weldability—make them suitable for an array of demanding applications, including shaft forging, gear forging, crankshafts, connecting rods, and die forgings.

By manipulating these alloying elements, steelmakers provide engineers and buyers with a broad selection of forgeable steel grades tailored to virtually every performance and environmental requirement encountered in the metal forging industry.

Choosing the ideal steel alloy for forging is a critical process that blends technical knowledge with practical evaluation of performance requirements, processing constraints, and cost considerations. Making the right selection ensures finished products achieve maximum reliability and longevity, reduces waste, and maintains cost-effectiveness for both custom and high-volume forging operations.

Additionally, engineers and purchasing teams are encouraged to partner closely with material suppliers and specialty steel forging manufacturers to identify steel grades that have been laboratory-tested and certified for their intended application. Conducting research into available data sheets, material test reports, and case studies provides valuable insights into real-world performance and helps avoid costly mistakes in alloy selection. For further technical support, many steel forgers offer consultation services to guide clients in evaluating and sourcing the right forging steel alloys for their industry needs.Learn more about types of steel for forging.

Forging steel uses compressive forces to shape metal, resulting in a refined grain structure, higher solidity, and enhanced uniformity. This distinguishes forged steel from cast steel and makes it stronger, with better fatigue resistance and fewer imperfections.

Temperature determines the forging method: hot forging occurs above 900°C for ductility, cold forging at room temperature for precision, and warm forging at moderate temperatures for a balance of strength and formability. The chosen temperature impacts material properties and process requirements.

Common alloying elements in forging steel include boron, chromium, molybdenum, manganese, nickel, silicon, tungsten, and vanadium. These elements enhance properties such as strength, hardness, corrosion resistance, and ductility for various industrial applications.

Steel for forging is alloyed by melting base metals, annealing, descaling, further heating, and casting into billets. Each step—including controlled heating and hydrofluoric acid cleaning—ensures a consistent microstructure and removes impurities for high-integrity forgings.

Finishing methods for forged steel include grinding, flash removal, polishing, CNC machining, and shot blasting. These techniques eliminate surface defects, achieve tight tolerances, and enhance corrosion protection before further surface treatments like plating or coating.

In North America, SAE-designated alloy and carbon steels—including nickel, chromium, molybdenum, and vanadium steels—are common for high-performance forging, aligned to rigorous industry standards and application requirements in sectors like aerospace, automotive, and oil & gas.

Selecting a steel supplier can be challenging, time-consuming, and complex due to the numerous options available. While the internet is a valuable tool for researching suppliers, it is essential to consider additional factors to ensure a successful choice.

During the initial selection process for a steel supplier, obtaining a sample of the steel they produce is crucial to ensure it meets the quality standards required for forging and final products. Most reputable suppliers will have ISO certification to verify their product quality. Additionally, researching the company’s background and rating is important, as some companies may engage in inappropriate business practices.

Pricing is a crucial factor as it directly affects the cost of the final product. Most manufacturers provide clear pricing guidelines and offer cost analyses to help determine the appropriate type of steel and its suitability for the product being produced. However, in rare cases, a company might engage in price gouging by frequently adjusting its costs and prices.

Customer service is a central concept in modern business, significantly impacting the relationship with customers and the quality of the product. Often, customers are willing to pay a premium for steel when exceptional customer service is provided. Effective customer service is fundamental to manufacturing, ensuring assistance is available under all conditions and at all times. This aspect of business is crucial for transforming a single transaction into a lasting partnership and relationship.

In the steel supplier market, a select group of highly qualified suppliers are known for delivering high-quality products at reasonable prices. While the internet can offer basic information about a company, including its website, the most reliable way to assess a supplier’s credibility is by contacting their previous customers. Even if there are negative reviews, it's important to consider how the supplier addressed and responded to those concerns.

During initial negotiations with a supplier, it is crucial to specify the details of how and when the steel will be delivered. The condition in which the steel arrives can be a decisive factor in choosing a supplier, based on the application’s needs. Additionally, the type of steel and alloy affects turnaround times, as some alloys require longer processing periods.

With steel production rapidly increasing, reaching millions of tons per month, selecting a supplier that precisely meets your needs becomes crucial. Thorough consideration and planning are essential for ensuring a successful and profitable partnership.

Forging steel is a cornerstone of the metalworking industry, with a history spanning centuries in the production of high-tolerance, quality products. Initially, metal forging involved blacksmiths using an anvil and a heated forge, where they hammered heated metal into shapes for swords, cookware, battle shields, and other items. Over time, the process has advanced significantly with the introduction of modern technology and specialized equipment, enhancing both efficiency and precision.

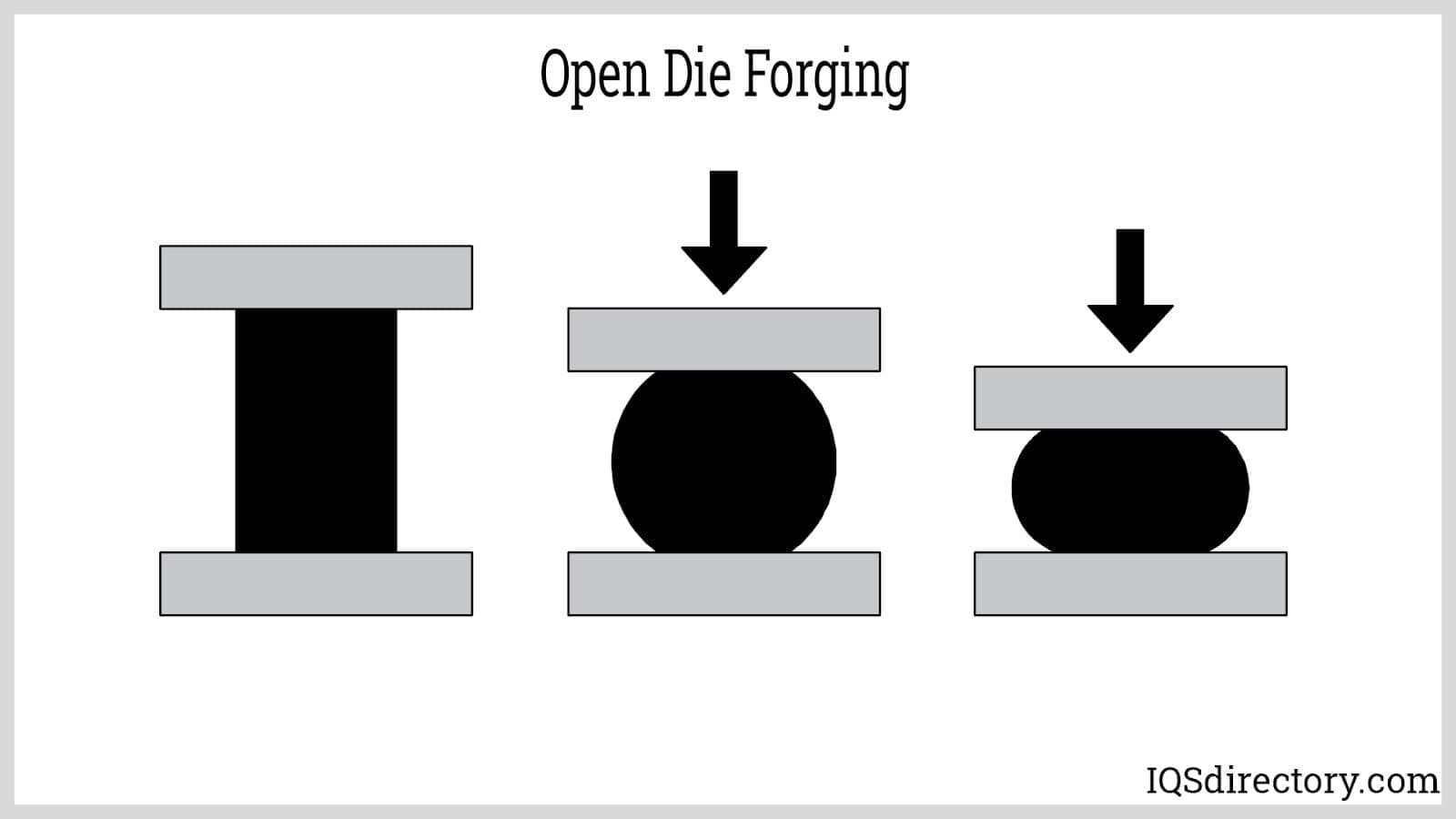

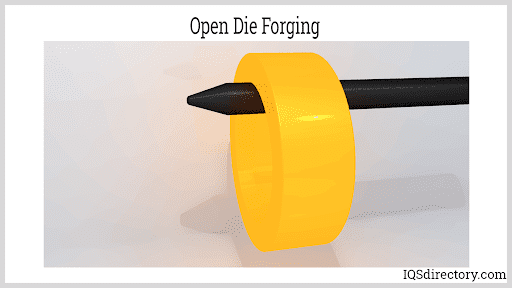

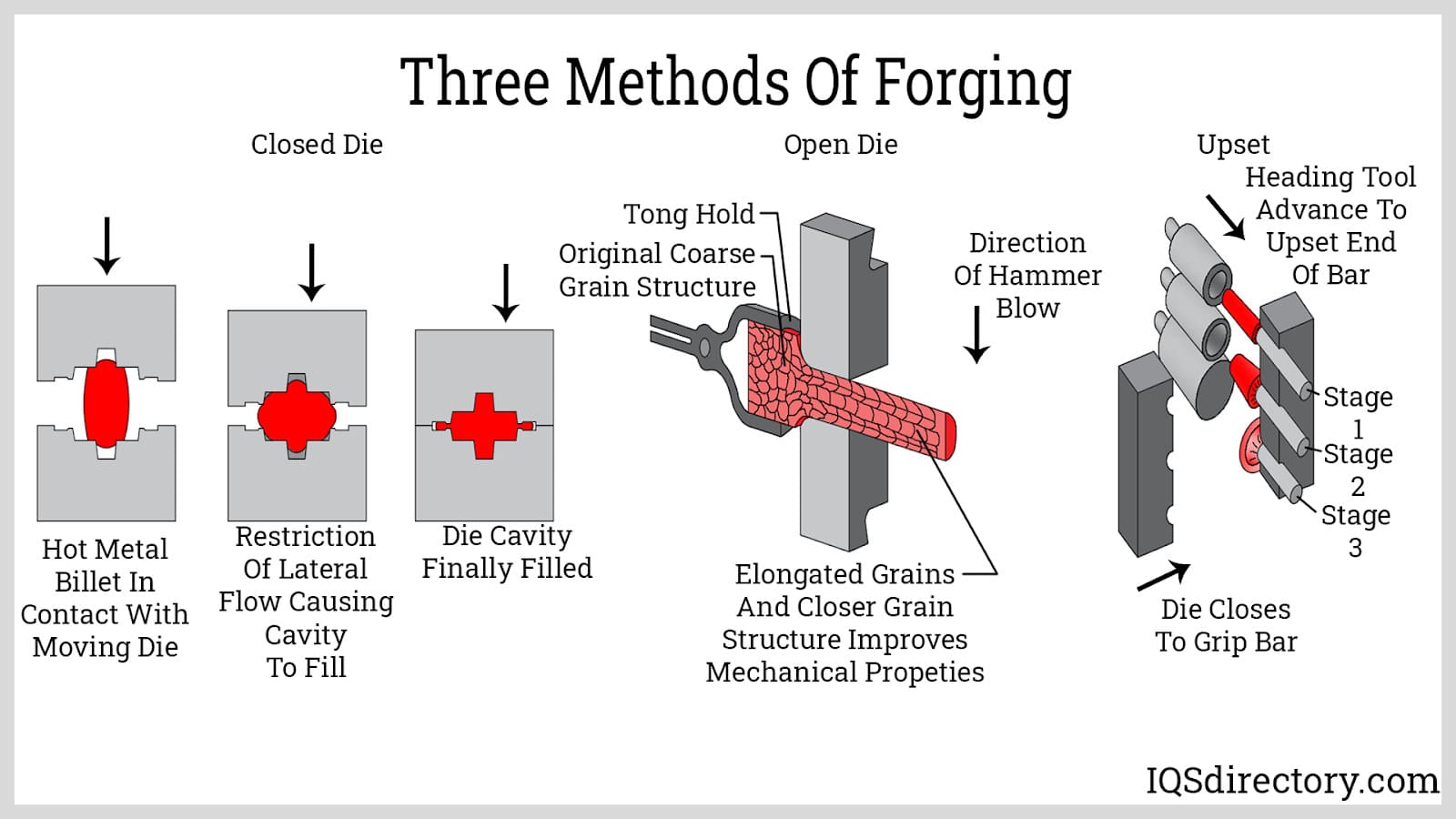

Open die forging involves deforming steel by placing it between dies that do not enclose the steel. The shape of the billet is changed by hammering or stamping it by a series of repetitions with each blow to the steel billet changing its shape. The workpiece is shaped between the top ram and a die that is placed on the bottom anvil. It is an imprecise forging method used for shaping simple forms. Once the process is completed, the forged piece requires a significant amount of machining.

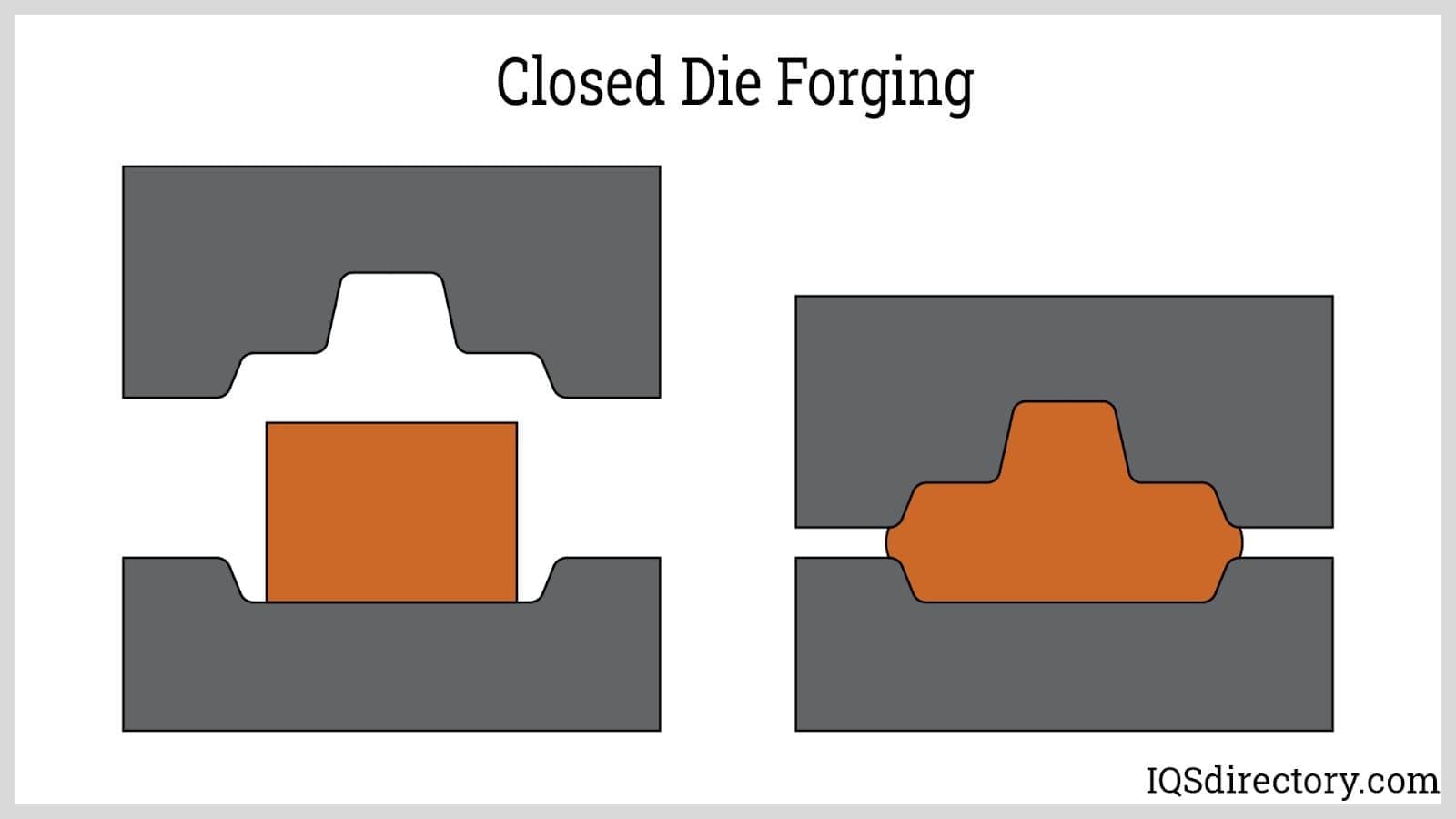

Closed die forging, also known as impression die forging, is employed to produce small to medium-sized components. This plastic deformation process involves forcing carbon steel between two halves of a die, allowing for the creation of intricate parts with complex geometries. The key to this process is the shaping and forming of the die itself, which requires a complex machining process to achieve the desired results.

In closed die forging, the bottom part of the die is fixed to an anvil, while the hammer portion repeatedly strikes the die cavity to shape the billet. The force of these repeated blows pushes excess material, known as flash, out of the die. This flash cools quickly, preventing additional flash formation and acting as a barrier to keep the steel from escaping the die, ensuring that the steel fills the die cavity completely.

In industrial closed die forging, the workpiece is processed through a series of dies. The initial die is used to distribute the metal and create a rough shape of the workpiece, often through fullering, edging, or bending impressions. Subsequent die cavities, known as blocking cavities, are designed to progressively refine the shape, each one resembling the configuration of the final product.

The forging load must be precisely calibrated to ensure the final product achieves the correct form. If the load is too low, the carbon steel will not fully conform to the shape of the die. Conversely, if the load is too high, it can overstress the steel, resulting in cracking and improper deformation.

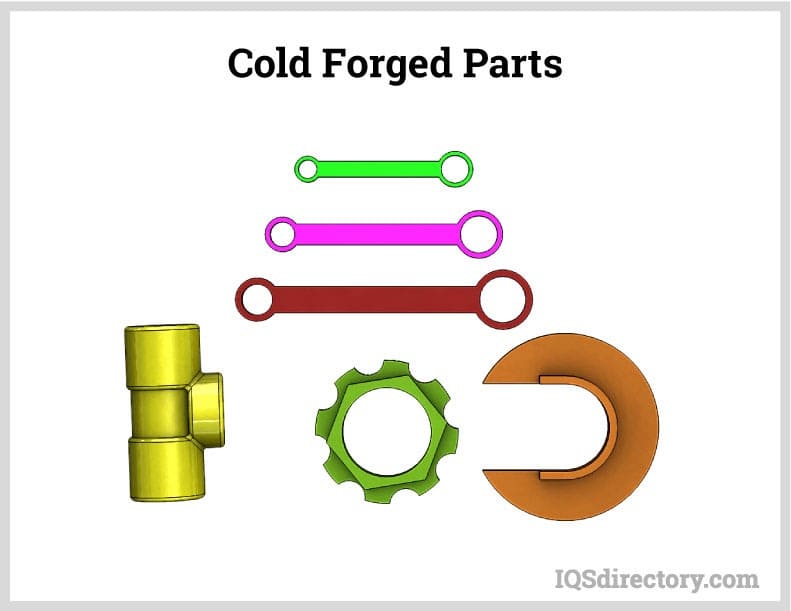

Cold forging deforms steel at or near room temperature, below its recrystallization temperature. This lower temperature makes the forging process more challenging, requiring greater energy and force. Because the steel billet is brittle at this temperature, it is prone to cracking during forging. However, cold forging compresses and elongates the steel grains, enhancing their strength and resilience.

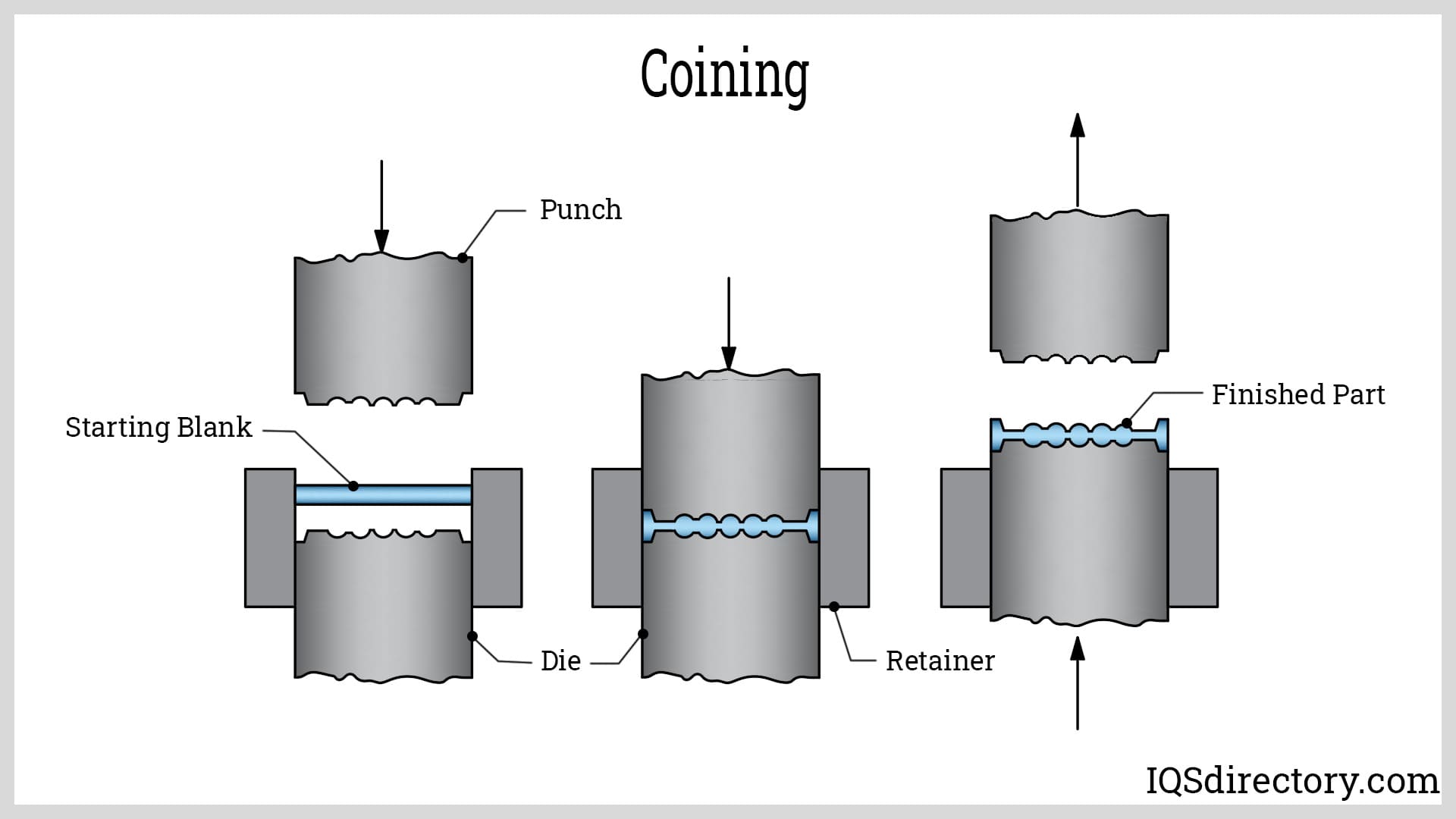

The basis of cold forging is impacting the workpiece to plastically deform it, under compressive forces, where the workpiece is located between a die and a punch. It is a displacement process that takes the workpiece and forces it into a desired shape. Some of the techniques of cold forging are extrusion, coining, upsetting, and swaging, each of which can take place in the same stroke or separate strokes.

Roll forging, also known as roll forming, utilizes cylindrical or semi-cylindrical rollers with grooves to shape and form steel. As the round or flat bar stock passes between these rollers, its thickness is reduced while its length increases. Roll forming can be performed with either cold or hot bar stock, though hot bar stock is often preferred. In the heated process, the bar stock is sufficiently heated to make it malleable and ductile, allowing for easier shaping. The grooves in the rollers are precisely designed to match the final part’s geometry, forging the workpiece to the correct dimensions.

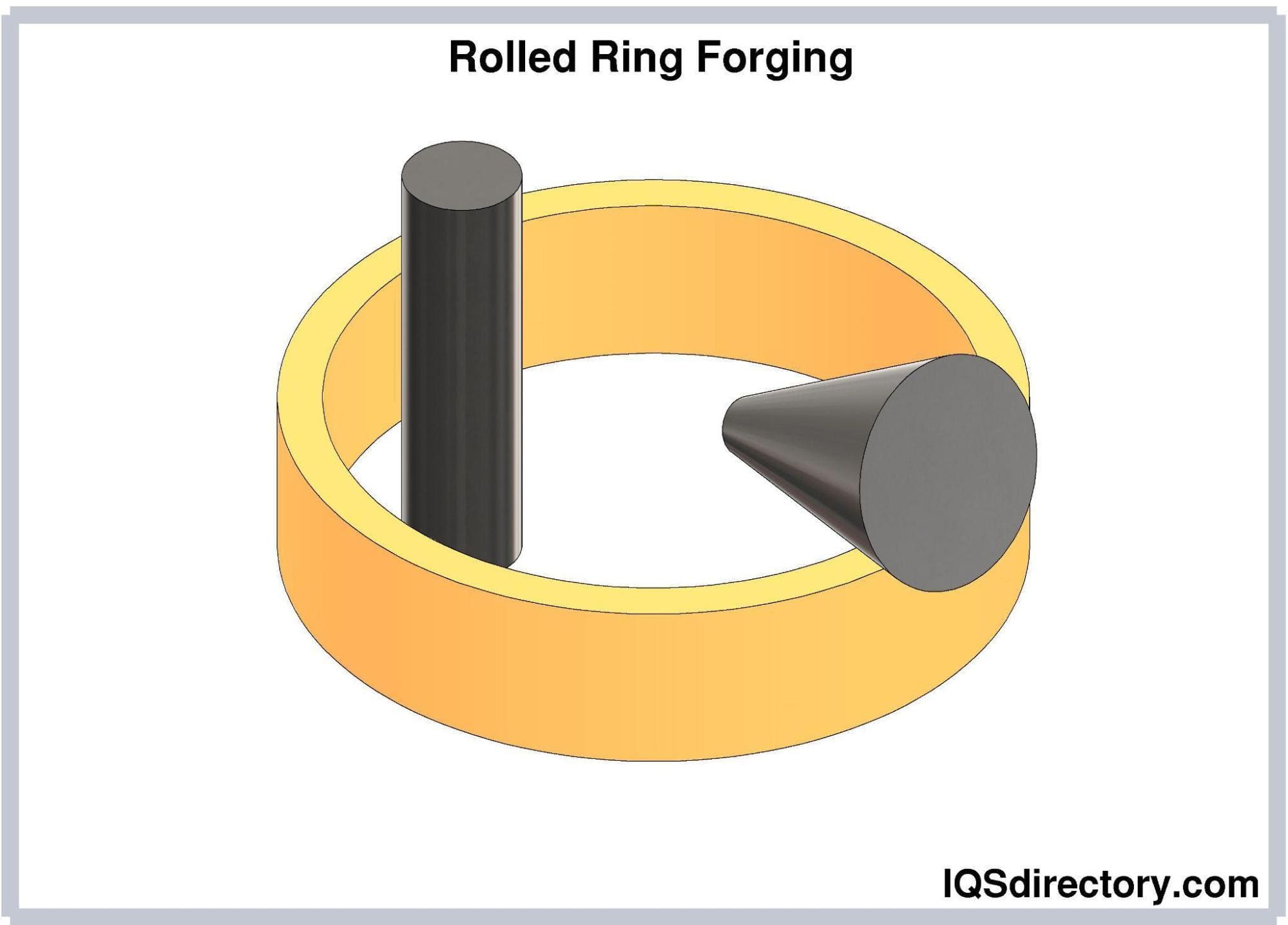

Ring forging is a distinctive type of roll forging that utilizes ring rollers to compress and reduce the size of a steel ring. This method eliminates the need for welding rings and produces rings with precise, uniform shapes.

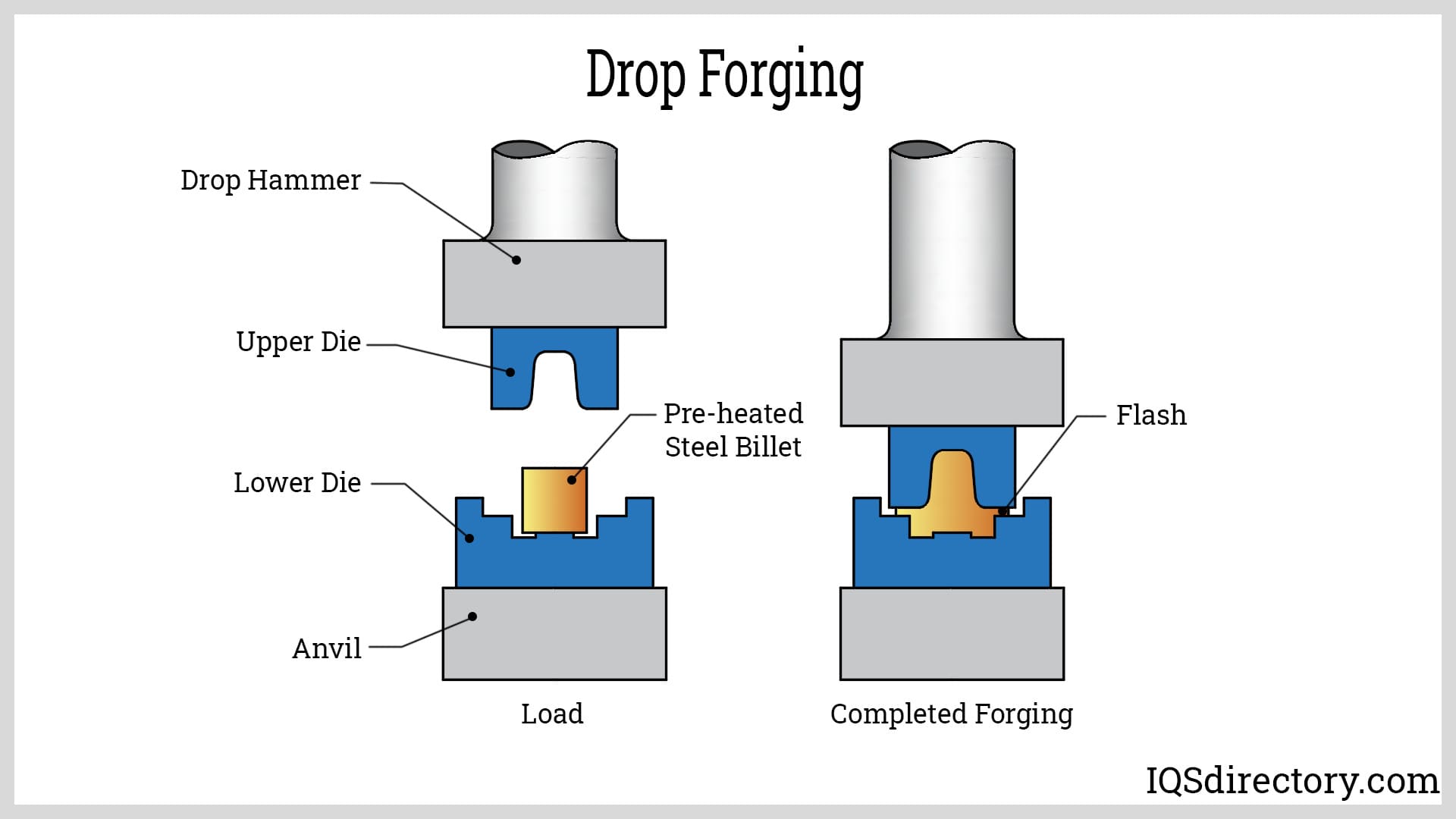

Drop forging uses impression dies and a heavy hammer to compress steel billets into designed shapes. A drop hammer that contains the upper die is a mechanical device that is powered by a pneumatic or hydraulic cylinder. The lower half of the die, as is found in open die forging, is attached to the anvil directly below the drop hammer. The steel billet is heated to a temperature that makes it malleable and placed in the lower die on the anvil.

The drop hammer exerts intense pressure on the steel billet, shaping it to fully occupy the lower die cavity. As the hammer impacts the die, excess material, known as flash, is expelled from the die impression. A draft angle is incorporated into the die design to facilitate the easy removal of the finished component.

Hot forging is a widely used method for forging steel, reminiscent of traditional blacksmithing with a hammer and anvil. By heating the steel, the process reduces the amount of force required to shape and mold the workpiece. The increased flow of heated steel makes it well-suited for both open and closed die forging. Additionally, the heating process anneals the workpiece, relieving internal stresses and preparing it for further processing.

In hot forging, the workpiece is heated to a temperature above its recrystallization point. During recrystallization, the original grain structure of the steel is deformed and replaced by new, stress-free grains that continue to grow until the original grains are eliminated. This process helps to counteract the effects of strain hardening. Typically, the recrystallization temperature is between one-third and one-half of the steel's melting point.

Hot forging allows for precise control over the steel's microstructure, enabling the fine-tuning of its strength and durability. This method is particularly beneficial in manufacturing processes that involve high static and dynamic loads, as it ensures that the final products meet demanding performance requirements.

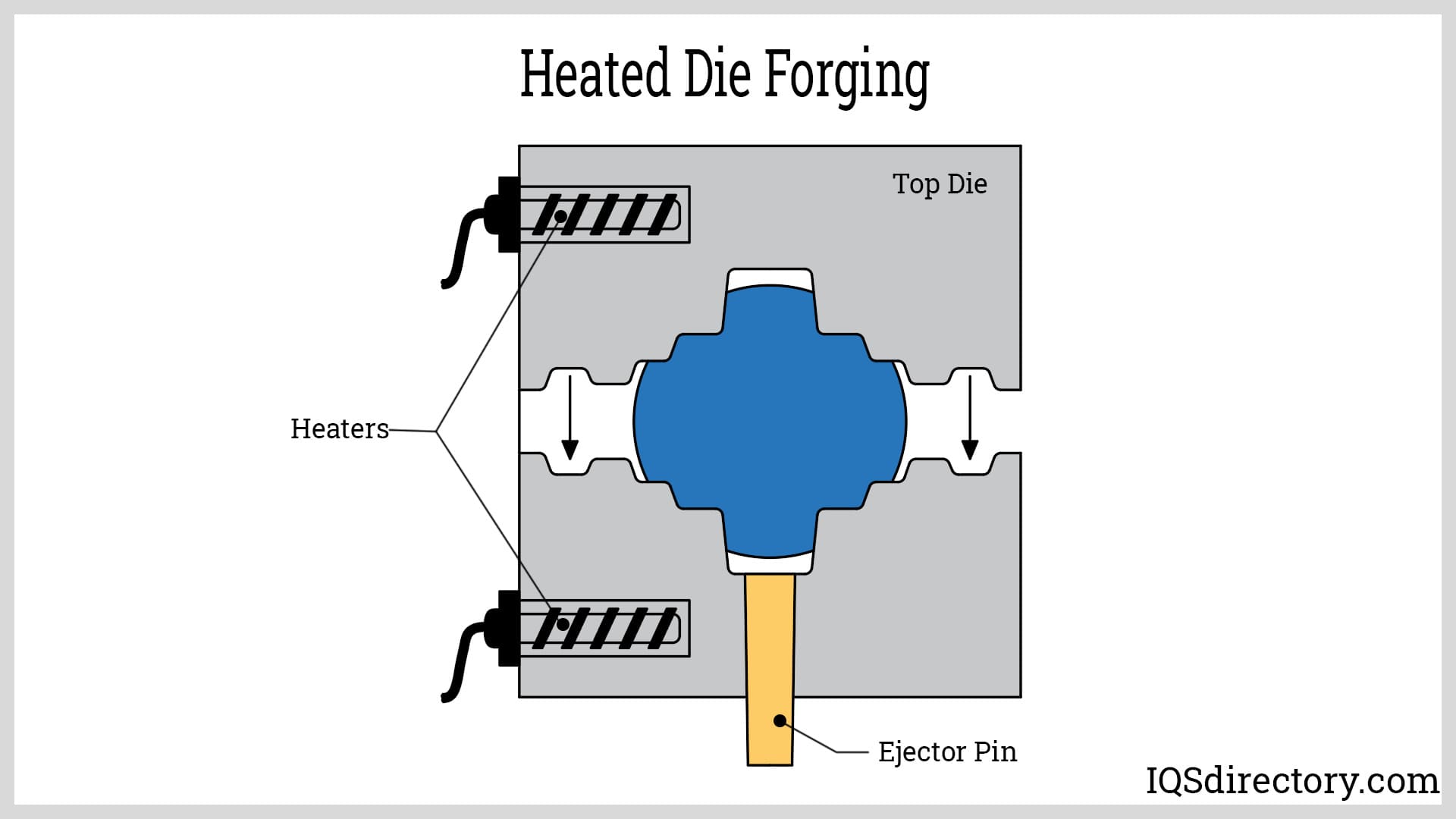

Heated die forging, a variation of hot forging, is used to achieve tighter tolerances, thereby reducing the need for machining and lowering steel costs. By utilizing a heated die, this method minimizes the number of preforming and blocking processes, which further decreases processing and tooling costs. Additionally, slower ram speeds can be employed to reduce the pressure required to form the workpiece.

Using cold dies can result in uneven plastic flow of the heated steel, a phenomenon known as die chilling. To prevent this, dies are heated to temperatures between 400°F and 500°F (205°C to 260°C) using furnaces or other methods, depending on the equipment. The most effective approach is to heat the die to match the temperature of the workpiece, a process known as heated or hot die forging.

Die heating is a crucial aspect of modern forging, with electric infrared heating being the most efficient method. Compared to gas or electric furnace heating, direct flame heating, electric calrod radiant heating, and gas radiant heating, infrared technology provides more uniform heating, eliminating hot or cold spots on the die. Additionally, the mobility of electric infrared heaters allows them to heat the die in place, ensuring continuous and consistent temperature control.

The term "steel" encompasses a broad range of alloys created by combining iron with carbon and other elements. The use of steel dates back to the Iron Age, when it was discovered that iron was stronger and harder than bronze. For centuries, iron production was heavily reliant on the quality of the raw ore and the methods used to produce it.

Over the centuries, the processes for producing steel were refined in regions such as China, India, Sri Lanka, Turkey, and Europe. By 2000 BCE, forged iron, with around 0.8% carbon, resulted in a hard but brittle form of steel. Metallurgists in Egypt and China discovered that heating this brittle steel, a process known as tempering, made it less brittle. The dynamics of steel production advanced significantly during the First Industrial Revolution, as hotter furnaces were developed to add carbon and produce stronger, more durable steel.

The main types of steel include low carbon steel, mild steel, carbon steel, and stainless steel. Mild steel is available in grades like A36 and 1018, with 1018 being the purest form. Carbon steel contains between 0.4% and 1.5% carbon. Stainless steel, known for its 10.5% chromium content, is available in martensitic and austenitic varieties, which can be either hardened or non-hardened.

Alloy steel is widely used in the steel forging process due to its enhanced strength, wear resistance, and toughness. This type of steel, based on iron, is mixed with other elements to improve its physical properties. Common alloying elements include chromium, molybdenum, manganese, nickel, vanadium, boron, and silicon. Some of the most commonly used alloy steels for forging include grades 4140, 4340, 6150, and 8620.

Alloy Steel 4140, which contains chromium, molybdenum, and manganese, is known for its excellent strength, toughness, ductility, and resistance to fatigue, abrasion, and impact. It maintains its performance and resists stress and creep at temperatures up to 1000°F (537.8°C). Additionally, 4140 is available in leaded grades that enhance machinability, although these leaded versions are less suitable for high-temperature applications due to reduced ductility.

The process of making alloy steel 4140 involves several steps. First, the alloying elements are placed in a furnace, where they are melted together. Once the molten steel cools, it undergoes annealing, often repeated multiple times to relieve internal stresses and refine the grain structure. After annealing, the steel is remelted and poured into molds. The resulting steel can then be subjected to hot or cold working to achieve the desired shape and properties.

Alloy 4340 is a nickel-chromium-molybdenum alloy renowned for its exceptional toughness, strength, and fatigue resistance. Heat treating 4340 further enhances its strength while preserving its toughness and wear resistance. Additionally, the heat treatment process provides improved resistance to atmospheric corrosion.

Alloy 4340 can achieve high strength levels up to 150 KSI 0.2% PS with proper heat treatment. It is often chosen over Alloy 4140 for its superior strength, better hardenability, and exceptional impact resistance. The heat treatment process is critical in the production of Alloy 4340, requiring careful monitoring to ensure the desired hardenability and performance characteristics are achieved.

Alloy 6150 is a low-alloy steel that includes carbon, small amounts of vanadium, and chromium, providing it with excellent shock resistance and toughness when properly heat treated. The addition of vanadium distinguishes it from Alloy 5150, enhancing its hardness. Key characteristics of Alloy 6150 include oil hardening, resistance to vibratory stress, medium hardness, and high torque strength. It also features low distortion properties and responds well to heat treatment.

Alloy 6150 is primarily utilized for manufacturing medium to large components that demand high tensile strength and toughness. Its applications include automobile parts like crankshafts, steering knuckles, connecting rods, spindles, gears, and gear shafts. This alloy is forged within a temperature range of 1600°F to 2150°F (870°C to 1175°C). For optimal results, it should be slow-cooled and annealed to enhance machinability.

Alloy 8620 is a nickel, chromium, and molybdenum steel alloy known for its exceptional strength and wear resistance. The nickel content imparts excellent core toughness. It is forged at temperatures ranging from 1700°F (925°C) to 2250°F (1230°C) and is air-cooled post-forging. After cooling, alloy 8620 is readily machinable and amenable to heat treatment. Its flexibility during hardening processes allows for significant enhancement of its core properties.

Due to its low carbon content, alloy 8620 cannot be hardened by flame or induction methods but is effectively hardened through nitriding. This alloy is widely utilized in applications that demand both toughness and wear resistance. Common uses for 8620 include gears, crankshafts, shafting, axles, bushings, pins, bolts, springs, hand tools, and various other machinery components.

The four steels listed above represent just a fraction of the many varieties used in the steel forging process. When selecting a steel for forging, the primary consideration is the temperature range at which the steel can be forged. Most steels can be forged within temperatures from 700°C to 1300°C (1290°F to 2300°F). The ductility of steel, influenced by its carbon content and alloying elements, varies accordingly. Steels with higher carbon content generally exhibit lower ductility and require higher temperatures to alter their grain structure.

| Steel Alloys for Forging Steel | |

|---|---|

| AISI | Description |

| 4130 | Forged in a temperature range of between 1750°F (954°C) and 2200°F (1204°C), Alloy Steel 4130 contains chromium and molybdenum (as strengthening agents) and can be hardened by heat treatment. |

| 4140 | Forged at a temperature range of between 1700°F (926°C) and 1900°F (1038°C), this alloy steel has a high fatigue strength, toughness, torsional strength and a resistance to abrasion and impact. |

| 4330 | Forgeable in the temperature range between 1800°F (982°C) and 2200°F (1204°C), Alloy Steel 4330 is heat treatable, in which it has a good strength, toughness and a good fatigue strength. |

| 4340 | Forging is typically done between a temperature range of 1800 °F (982 °C) and 2250 °F (1232 °C). Alloy Steel 4340 is a heat treatable low alloy steel and is know for its toughness as well as for its ability to develop a high strength in heat treated conditions while still retaining a good fatigue strength. |

| 8620 | A common carburizing alloy steel and its is flexible during heat treatment. |

| 8630 | A lot more responsive to mechanical and heat treatments when compared to carbon steels, this alloy steel is alloyed with a number of elements including manganese, chromium, nickel, carbon, silicon and molybdenum. |

| 9310 | Forged at a temperature range of between 1700 °F (927 °C) and 2175 °F (1191 °C), this alloy steel contains molybdenum, nickel and chromium. |

| Nitralloy 135 | Forged in a temperature range of between 2000 °F and and 2025 °F, this alloy steel has a moderate hardenability and is used in applications such as gears, bolts and crankshafts. |

| Carbon Steel for Forging Steel | |

|---|---|

| AISI | Description |

| 1010 | A carbon steel with a 0.10% carbon content, alloy 1010 has low strength, which can be improved by quenching and tempering. Forging can be completed at 1800°F (982°C) up to 2300°F (1260°C). |

| 1018 | A low carbon steel, alloy 1018 has good ductility, toughness, and strength. Its temperature for forging is 2102°F up to 2336°F (1150°C up to 1280°C). |

| 1020 | With a combination of ductility and strength, alloy 1020 can be hardened and carburized. It can be forged at between 1800°F (982°C) up to 2300°F (1260°C). |

| 1026 | Alloy 1026 contains high iron content at 98.73% up to 99.18% with carbon content of 0.22% up to 0.28% and manganese at 0.6% up to 0.9% |

The steel forging sector employs a distinct set of terminology to describe both the techniques and the quality of forged products. This specialized vocabulary covers every facet of the forging process. Below is a selection of terms commonly used in this industry.

Backward Extrusion - This technique involves directing a workpiece to move in the opposite direction of a punch or die's motion.

Blast Cleaning - A method of finishing and cleaning parts using abrasive materials like grit, sand, or shot.

Board Hammer - This process involves hardening a workpiece's surface while keeping the core soft. Methods include carburizing, carbonitriding, cyaniding, and flame hardening.

Cold Shut - A defect on the surface where the forged metal folds over itself, typically occurring at intersections of vertical and horizontal surfaces.

Compressive Strength - The maximum pressure a metal can endure without fracturing or permanently deforming.

Descaling - The removal of scales from a workpiece using wire brushes, water spray, and gentle impacts.

Draft - Excess material on the side of a workpiece that assists in its removal from a die.

Drawing - A forging technique that reduces and lengthens metal stock using flat dies.

Dye Penetrant Testing - An inspection method using liquid dye to reveal flaws in materials.

Elastic Limit - The maximum stress a metal can tolerate before it undergoes permanent deformation.

Electroslag Remelting (ESR) - A pre-forging process where steel is remelted through slag to enhance uniformity and improve its properties.

Finish Allowance - The amount of material left on a workpiece's surface that will be removed during the finishing process.

Heading - A forging process that forms heads on the ends of rods and wires.

Inclusions - Nonmetallic particles found in ingots that can affect the metal's directional properties based on their shape and distribution.

Lap - A defect characterized by a seam on the surface of a workpiece, resulting from folding over or sharp edges.

Magnetic Particle Inspection (MPI) - A testing method for detecting surface and subsurface defects in magnetic metals such as nickel, iron, and their alloys.

Normalizing - A heat treatment process where a workpiece is heated above its transformation temperature and then cooled to refine its structure.

Reduction in Area - A measurement from a tensile ductility test indicating the difference between a workpiece’s original cross-sectional area and its smallest cross section after testing.

Segregation - The uneven distribution of alloying elements that occurs during solidification.

Shrinkage - The contraction of metal due to cooling after hot forging.

Superalloys - High-performance alloys based on iron, nickel, or cobalt, known for their superior high-temperature mechanical properties and oxidation resistance.

Ultrasonic Testing - A method using ultrasonic waves to identify structural defects.

Steel forging companies all claim to have the most efficient and effective processes and procedures in the market, which can make it challenging for customers to choose one that aligns with their project requirements. Experts in steel forging have provided valuable tips for selecting the right forging company.

When considering steel forging, cost is typically the primary concern in industrial processes. However, opting for the least expensive option may not always be the wisest choice. A comprehensive evaluation of a producer should encompass factors beyond just cost.

During sales pitches, emphasis is often placed on turnaround times. To gain a clearer understanding of actual turnaround times, it's crucial to request specific information about recent orders: when they were placed, when they were completed, and when they were delivered. It's also important to inquire about the delivery process for the final product. While some companies excel in turnaround times, they may lack an efficient delivery system.

When considering turnaround times for forging steel parts, one critical aspect is the timeline required for the actual forging process. This timeline also encompasses the duration needed to create tooling specific to the forging process. For unique or uncommon parts, a significant amount of time is often necessary to fabricate the dies, which consequently increases the overall forging lead time.

The complexity and size of a forging significantly influence several factors: the choice of forging process, the design of dies, the selection of a forging company, and ultimately, the cost of the forging. More complex parts often necessitate additional finishing and machining operations, which extend the timeline and increase the overall turnaround time.

Experienced steel forging companies, with years of industry involvement and a solid reputation, possess a deep understanding of handling forgings that feature unique requirements. Throughout the project development process, these seasoned companies can offer dependable information on turnaround times, tooling requirements, and effective delivery methods.

Highly qualified steel forging companies undergo rigorous vetting, certification, and legal approval processes. The majority of reputable companies hold International Organization for Standardization (ISO) certification, which mandates adherence to specific guidelines for customer service and processing standards in order to achieve certification.

In modern industrial businesses, what distinguishes successful companies from average ones is primarily customer service. This aspect of manufacturing processes has become pivotal in attracting customers and achieving long-term success. While pricing may initially attract customers, it is customer service that fosters lasting relationships and sustains ongoing sales. The quality of service, responsiveness to issues, and adaptability to change are key factors that contribute to building a reputable brand and ensuring sustained success.

Like many industries, steel forging has seen significant technological advancements that have revolutionized its processes. Outdated and dusty operations of the past have given way to modern, innovative methods that enhance efficiency and yield high-quality products. Evaluating these technological advancements is a critical aspect of the selection process, often included in factory tours or presentations to provide a comprehensive understanding of a forging company's capabilities.

Steel forging remains a fundamental process essential for manufacturing a broad spectrum of highly durable products across diverse industries. Despite its ancient origins, forging continues to be a cornerstone for producing superior quality components and parts. Its ability to impart desirable physical characteristics at a competitive cost sets it apart from other metalworking methods.

The objective of forging steel is to alter its grain structure through percussive or compressive forces, resulting in components that exhibit increased strength, toughness, and reliability. When heated or cold steel is compressed, it undergoes metallurgical recrystallization, which reconfigures the grain structure to yield exceptionally resilient and dependable parts.

High-capacity compressors form the backbone of ethylene plants, requiring forged steel parts that resist hydrogen sulfide compounds and endure high-pressure environments. These forged components are essential in petroleum and chemical facilities for their robust strength and reliability.

Forging steel hand tools is a longstanding practice that has endured for centuries. Pliers, hammers, sledges, wrenches, garden tools, sockets, hooks, turnbuckles, and eye bolts are all crafted through steel forging. Additionally, surgical and dental instruments, as well as hardware for electrical applications like pedestal caps, suspension clamps, sockets, and brackets, are forged for their robustness, reliability, and corrosion resistance.

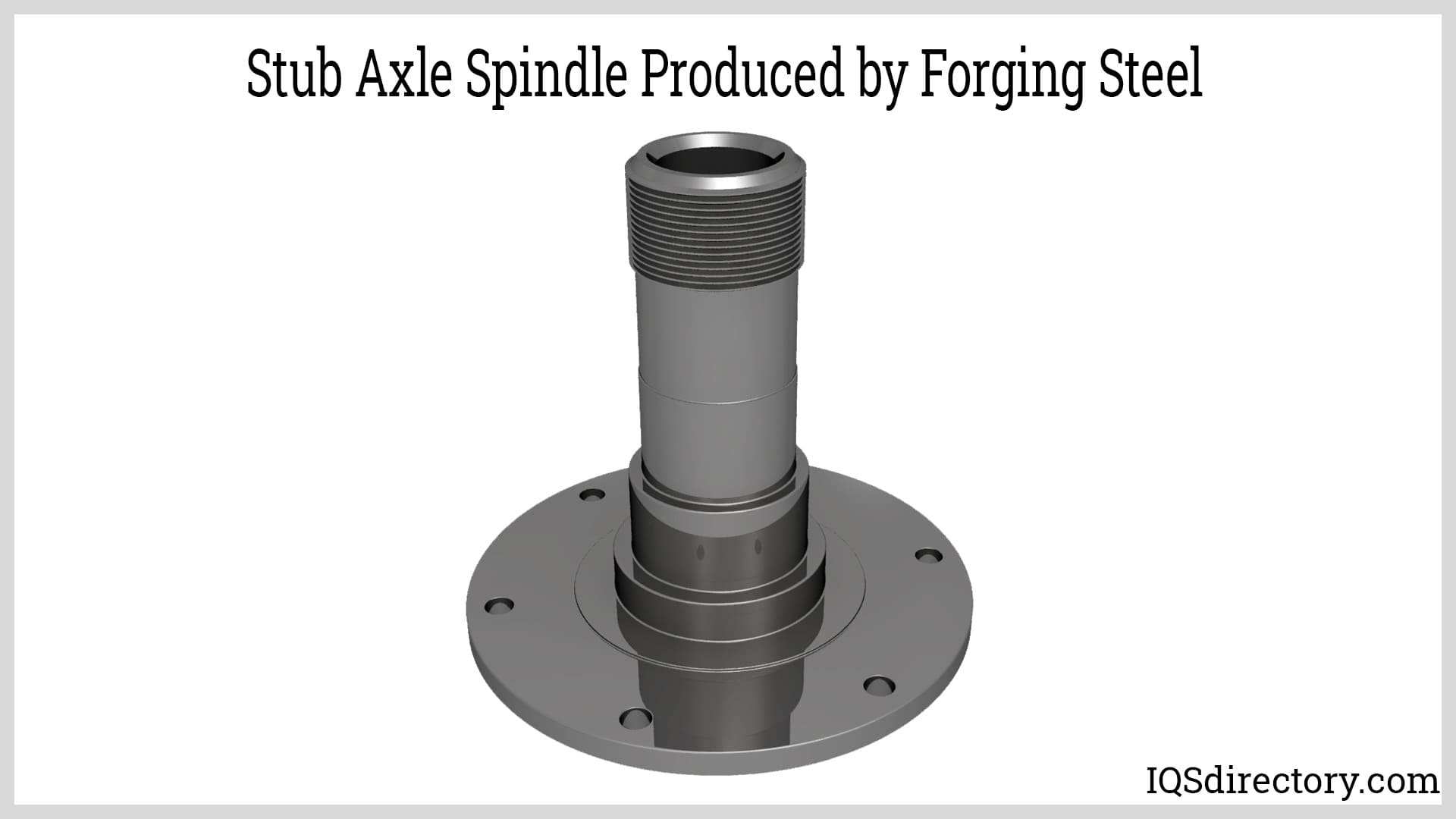

The structural integrity of modern automobiles and trucks heavily relies on components crafted through steel forging. This dependency stems from the superior strength, reliability, and cost-effectiveness of forged parts. These components are crucial in areas subjected to high shock and stress, such as wheel spindles, kingpins, axle beams, shafts, torsion bars, ball studs, idler arms, pitman arms, and steering arms.

Another essential application where forging steel is a necessity is in the powertrain, where connecting rods, transmission shafts and gears, differential gears, drive shafts, clutch hubs and universal joints are forged. Each of these components are produced using alloy or carbon steel due to its cost and reliability.

One of the most significant breakthroughs in history was the transformation of iron into plowshares. For centuries, farmers grappled with wooden plowshares that lacked the strength and durability to endure continuous use. The advent of iron plowshares, crafted by blacksmiths, marked a pivotal advancement. It allowed farmers to labor for years without the concern of frequent equipment replacement.

Forging steel is crucial for farmers due to its strength, toughness, and cost-effectiveness. Engine and transmission components in heavy-duty farm equipment rely on forgings that withstand impact and fatigue, including gears, shafts, levers, spindles, and tie rod ends. Among all industries, forging has had the most profound impact on farming and food production.

Forged steel's strength makes it indispensable for manufacturing valves and fittings designed for high-pressure applications. Its superior mechanical properties and absence of porosity render it ideal for critical components in the oil and gas industry. Steel's corrosion resistance and ability to withstand heat are also crucial factors for components like flanges, valve bodies, stems, tees, elbow reducers, saddles, and other fittings. In oil field applications, forged steel is used extensively for rock cutter bits and drilling hardware due to its durability and reliability.

An intriguing historical tidbit often overlooked is that the original railroad tracks were initially constructed from wood, which proved inadequate for withstanding the stresses imposed by steam engines. In an effort to address this issue, iron was overlaid onto the wooden tracks to improve their durability. However, this solution ultimately proved unsuccessful. It wasn't until the first industrial revolution and the advent of steel forging that modern railroad tracks took shape. These tracks are now crafted from highly durable alloy and carbon steel, marking a significant advancement in rail infrastructure.

In the railroad industry, the use of forging steel has expanded into a wide range of components including anchor shackles, ball bearings, ball joints, beam clamps, bearings, blocks, bolts, clips, chain links, chain pullers, chain shackles, chain slings, chokers, clamps, claws, engine components and parts, and fasteners. The list continues into hundreds of parts, pieces, components, and features that keep the world’s railroads running.

In ship construction, a variety of metals are employed, yet steel stands out as the most universally favored material. Its strength and reliability make it optimal for manufacturing high-quality components that withstand fatigue and endure the lifespan of a ship. Forging steel, utilizing advanced technology, is the most dependable method for producing the diverse parts required for ships.

Forged steel plays a vital role in the construction of spacecraft and airplanes, relying on its durability and strength. Unlike in other industries where weight may not be a critical concern, aerospace manufacturing demands lightweight materials. Despite steel being inherently heavy, it can be forged and processed to meet the stringent weight requirements for aircraft construction. Aerospace components such as cross-rolled sheets and plates, turbine rings, bearing rings, fuselage structures, and rotor blades for helicopters are all manufactured using steel forging techniques.

Forging steel demands the utmost engineering expertise and meticulous production control. It has been established that forging steel surpasses steel casting or machining from bar stock due to its unique grain flow, which conforms naturally to the shape of the products. This inherent grain flow enhances the material's performance in handling tensile and shear loads, making forged steel superior in strength and reliability for various applications.

Aluminum forging is a method for processing aluminum alloys using pressure and heat to form high strength, durable products. The process of aluminum forging involves pressing, pounding, and...

Cold forging is a metal shaping & manufacturing process in which bar stock is inserted into a die and squeezed into a second closed die. The process, completed is at room temperature or below the...

Copper and brass forging is the deformation of copper and brass for the purpose of manufacturing complex and intricate shapes. The temperature at which copper and brass are forged is precision controlled and...

Forging is a metal working process that manipulates, shapes, deforms, and compresses metal to achieve a desired form, configuration, or appearance outlined by a metal processing design or diagram...

In this article, there are key terms that are typically used with open and closed die forging and it is necessary to understand their meaning. Forging is a process in manufacturing that involves pressing, hammering, or...

Rolled ring forging is a metal working process that involves punching a hole in a thick, solid, round metal piece to create a donut shape and then squeezing and pressuring the donut shape into a thin ring...

The ancient art of forging falls into two distinct categories – hot and cold where hot forging has been around for centuries while cold did not begin until the industrial revolution of the 19th Century. Though they are quite different ...

Aluminum casting is a method for producing high tolerance and high quality parts by inserting molten aluminum into a precisely designed and precision engineered die, mold, or form. It is an efficient process for the production of complex, intricate, detailed parts that exactly match the specifications of the original design...

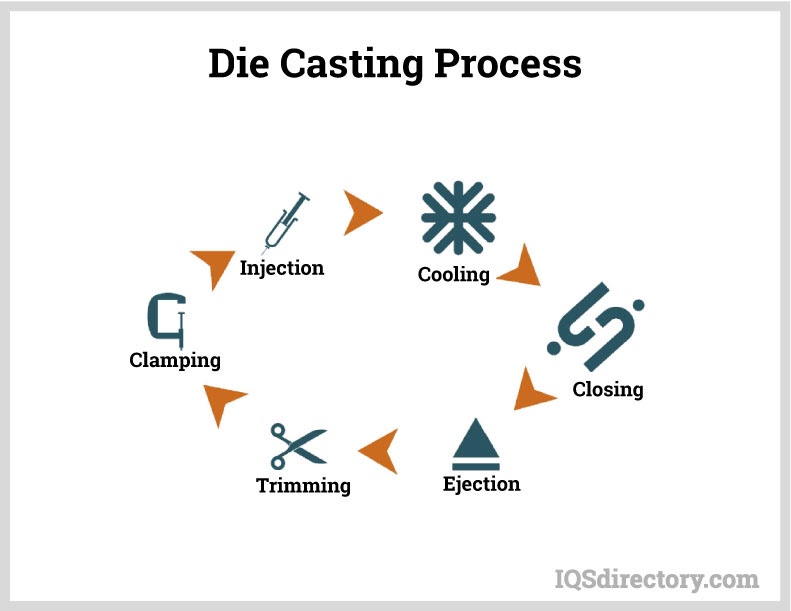

Die casting is a high pressure metal casting process that forces molten metal into a mold. It produces dimensionally accurate precision metal parts that have a flawless smooth finish...

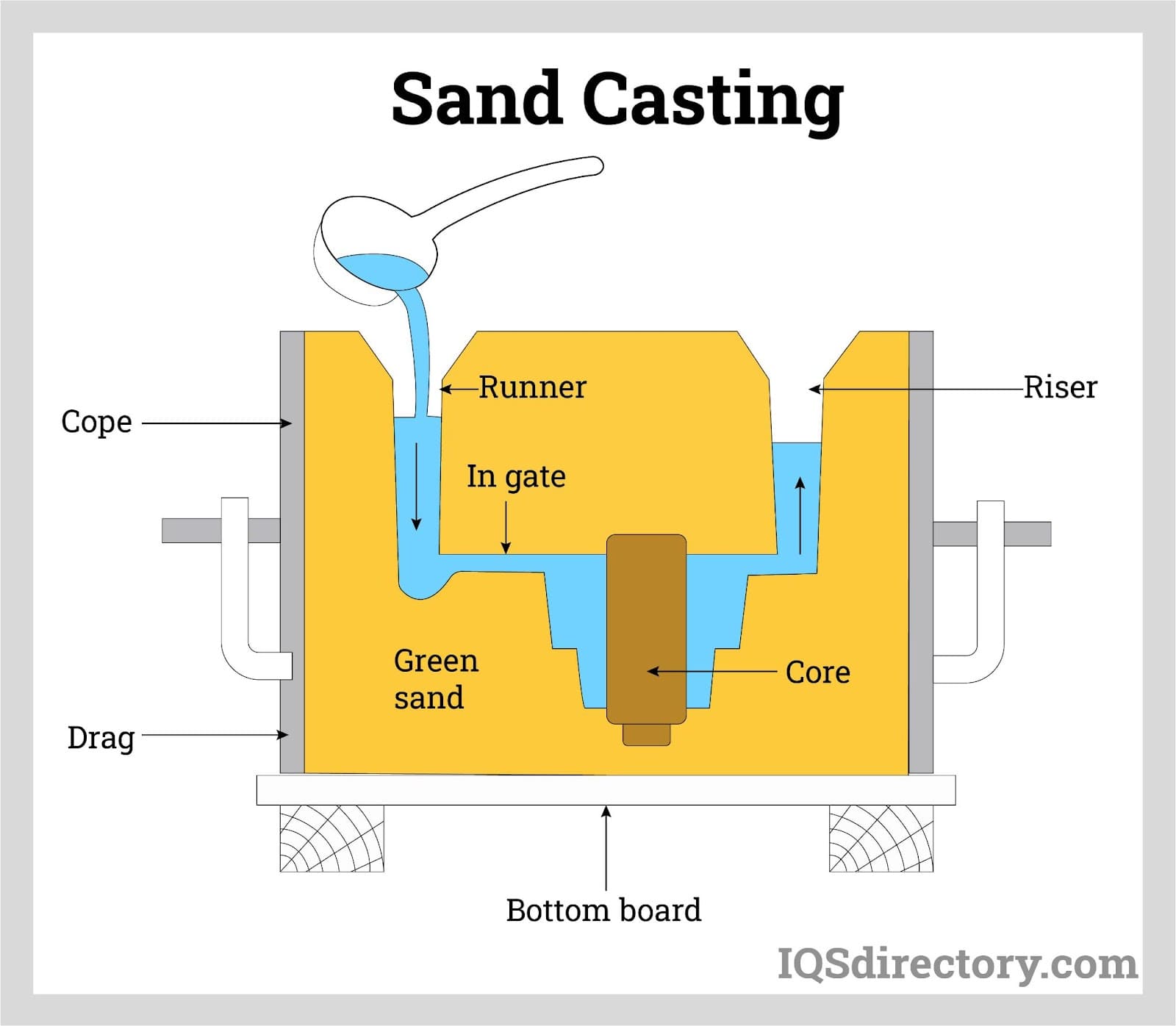

Sand casting is a manufacturing process in which liquid metal is poured into a sand mold, which contains a hollow cavity of the desired shape and then allowed to solidify. Casting is a manufacturing process in which...

Zinc die casting is a casting process where molten zinc is injected into a die cavity made of steel that has the shape, size, and dimensions of the part or component being produced. The finished cast zinc product has...

The casting process is an ancient art that goes back several thousand years to the beginning of written history. The archeological record has finds that document the use of the casting process over 6000 years ago around 3000 BC or BCE...